Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

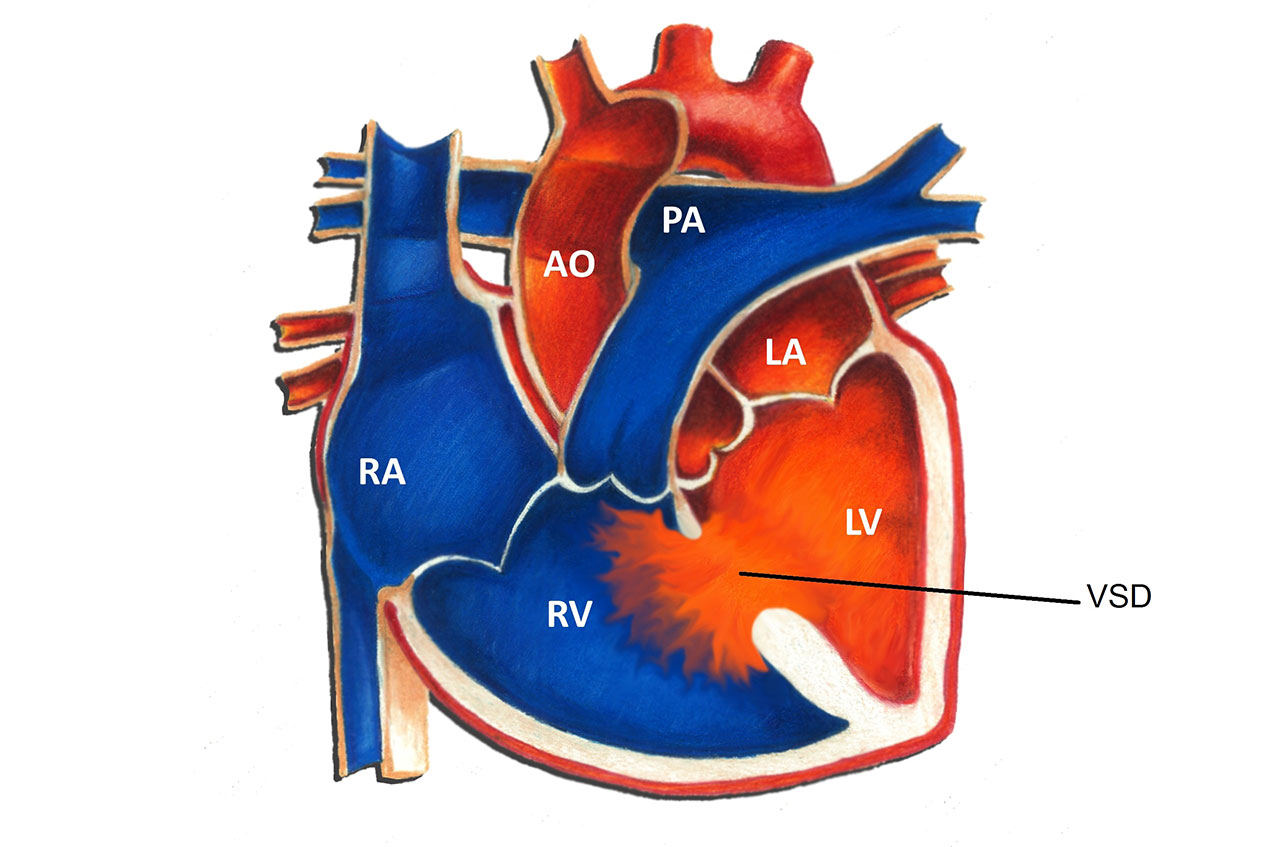

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a hole in the ventricular septum, the lower wall of the heart separating the right and left ventricles. A VSD is a congenital heart defect, in other words, a birth defect of the heart. Congenital heart defects are the most common form of birth defects, occurring in approximately 1 in 150 individuals. A VSD is the most common congenital heart defect; the overall incidence is 3-4 per 1000. There are many different types of VSD’s. The most common type, termed a muscular VSD, is formed when the muscle of the wall fails to completely seal. The majority of muscular VSD’s are very small and rarely of any physiologic consequence. Less common types of VSD’s include membranous, inlet and outlet types. These types of VSD's are often larger and may cause more problems for an infant or child.

Physiologically, a VSD allows for oxygenated blood (“red blood”) to pass from the left ventricle to the right ventricle, join with deoxygenated blood (“blue blood”), and return to the lungs. The net effect of a VSD is therefore an increase in the total amount of blood that flows to the lungs. The amount is primarily determined by the size of the VSD. A large VSD allows for a significant degree of blood flow to the lungs; a small VSD often results in a negligible increase.

Symptoms from a VSD are related to excess blood flow to the lungs. They are usually seen in patients with large VSD’s, but may be absent in the setting of moderate size defects. Small defects rarely if ever produce symptoms. The most common symptom is a rapid respiratory rate. This may be more obvious during times of exertion, such as feeding in an infant. Other symptoms in infants include sweating with exertion, poor feeding due to fatigue, and poor weight gain. VSD’s may also predispose to an increased risk of lung infections such as pneumonia.

Diagnosis of a VSD can be made in a number of different ways. A patient with a VSD usually comes to attention due to the presence of a heart murmur. This simply refers to the sound that blood is making as it flows through the hole from one chamber to another. There are many other different causes of heart murmurs, including normal causes. An echocardiogram uses sound waves to visualize the intracardiac structures and is the easiest way to diagnose the size and location of a VSD. Occasionally a heart catheterization may be necessary to assess the lung blood pressures or the amount of shunting through a VSD.

There is a wide spectrum of treatment options for a patient with a VSD. Between 50 to 75% of small muscular VSD’s detected in the first few months of life close spontaneously. Even in cases where a small VSD remains open, specific therapy is rarely needed. In patients with larger VSD’s who are symptomatic, medication may alleviate those symptoms. The most commonly used medicine is furosemide (Lasix), a diuretic that works by decreasing excess lung fluid caused by the extra blood flow to the lungs. Furosemide may be given anywhere from 1 to 4 times daily. Side effects are uncommon; abnormalities of electrolytes can occasionally be seen with larger doses. Another medication frequently used in the setting of a VSD is digoxin (Lanoxin). Digoxin increase calcium levels in heart cells, thereby improving overall heart function.

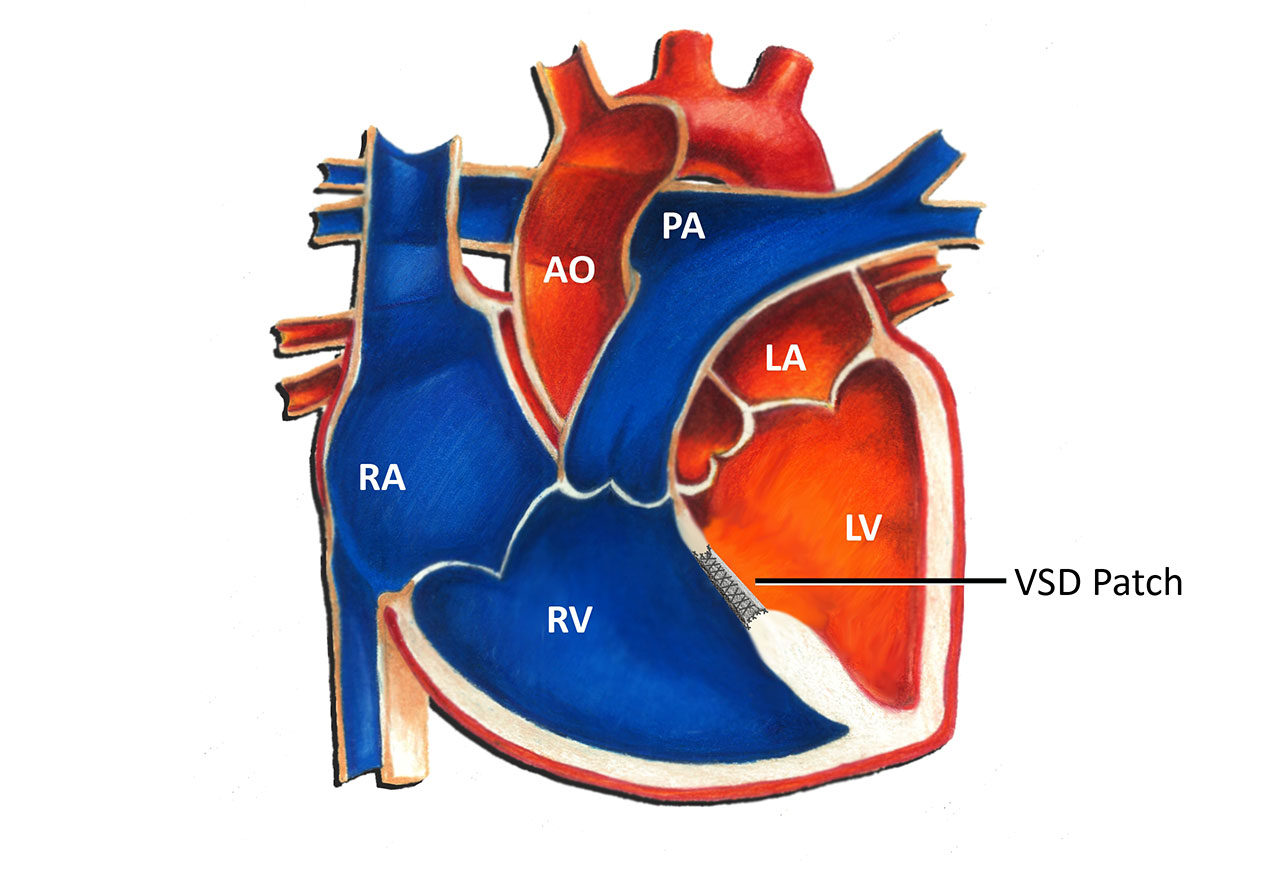

Surgery is occasionally necessary to close a VSD. This most commonly occurs in the setting of a large or moderate size defect. Indications for surgery in infancy include symptoms unresponsive to medication, elevated blood pressure in the lungs, and significant dilation of the heart due to excess blood flow. Usually the need for surgery in infancy becomes clear by 6-12 months of age, and often much earlier. Less common indications for surgery are infection of heart tissue due to the VSD, and damage to the aortic valve secondary to the VSD. The risk of surgery for a VSD in this day and age is relatively low. The vast majority of patients do very well with no significant long term problems. Typically a patch of synthetic tissue is used by the surgeon to close the VSD, as illustrated by the diagram below.

Up until recently, patients with any form of heart defect, including a VSD, were recommended to use antibiotics prior to dental work or surgery to minimize the risk of heart-related infection. However, in May 2007 the American Heart Association changed this recommendation such that now most patients with congenital heart disease, including those with a VSD, no longer require this precaution.