Ventricular Septal Defect - Surgical Repair

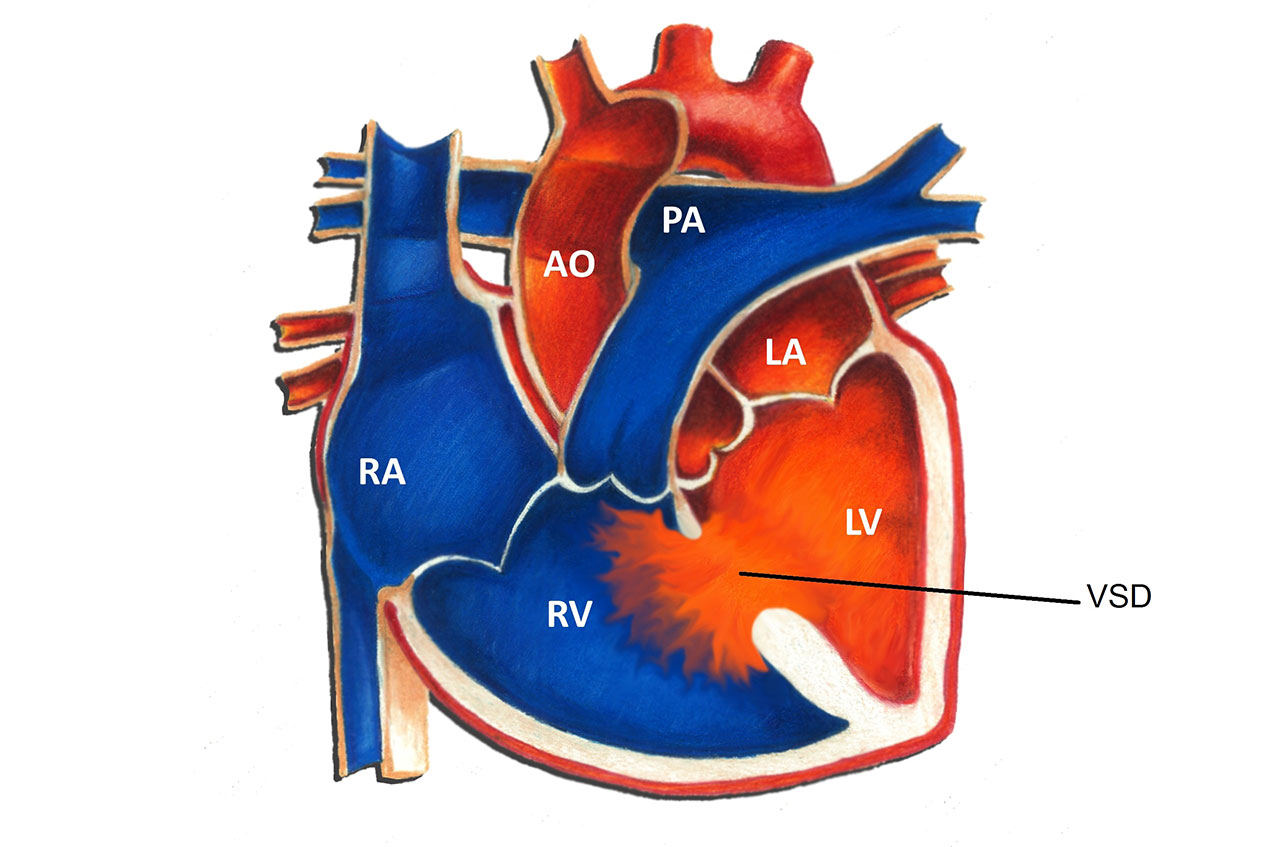

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a hole in the ventricular septum, the lower wall of the heart separating the right and left ventricles. Surgery is occasionally necessary to close a VSD. This most commonly occurs in the setting of a large or moderate size defect. Indications for surgery in infancy include symptoms unresponsive to medication, elevated blood pressure in the lungs, and significant dilation of the heart due to excess blood flow. Usually the need for surgery in infancy becomes clear by 6-12 months of age, and often much earlier. Less common indications for surgery are infection of heart tissue due to the VSD, or damage to the aortic valve secondary to the VSD.

The first successful surgery to close a VSD was performed in 1954 by C. Walton Lillehei and associates at the University of Minnesota. Since that time, surgical techniques and progress have improved tremendously. In this day and age, surgical closure of a VSD is generally considered a safe operation.

Because the hole created by a VSD is inside the heart, the heart must be drained of blood prior to any operation or manipulation. This requires the use of cardiopulmonary bypass. Cardiopulmonary bypass refers to the technique by which blood is diverted from the heart and lungs by a machine that subsequently removes carbon dioxide and supplies oxygen. Oxygenated blood is returned from the machine to the aorta. With the heart empty of blood, the surgeon is then able to safely open it, find the hole, and patch it closed.

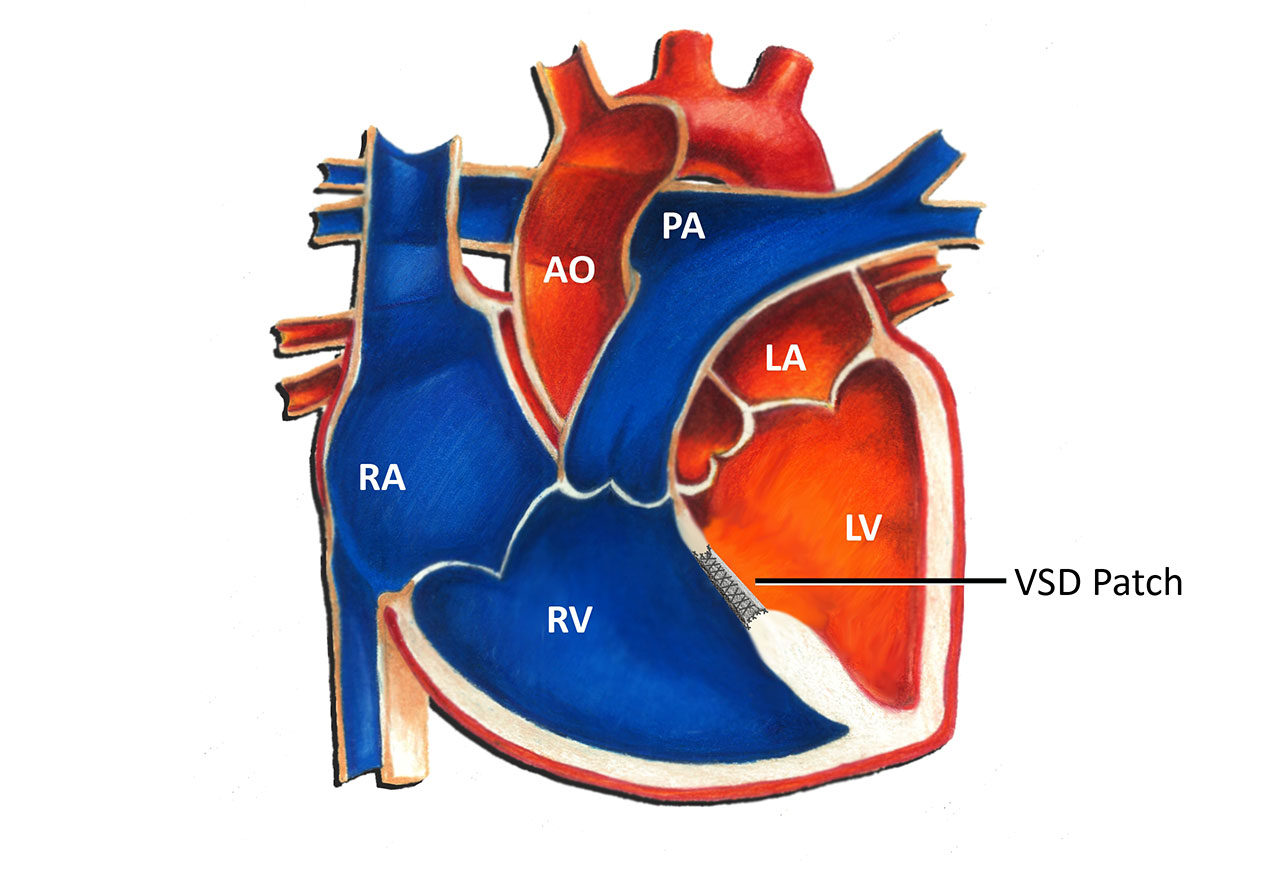

Typically a patch of synthetic material is used by the surgeon to close the VSD. The surgeon uses suture material to stitch the patch into place. Usually closing a VSD is relatively straightforward. However, in some instances the hole may be in a somewhat difficult to access location. Once the patch is sutured into place, the heart is closed and the patient is removed from cardiopulmonary bypass. Blood returns to the heart and the operation is complete at this point.

Fortunately over time the natural tissue of the heart grows over the VSD patch and seals it into place. Usually this process takes about 6-12 months. Because of this, the patch never has to be replaced or removed as a patient grows. Once a VSD is closed, it is typically closed for good!

On rare occasions some patients may be left with a small residual VSD after surgery. This often occurs when the VSD is in close proximity to the normal electrical conduction tissue. Sometimes in an effort to avoid the normal electrical conduction tissue the surgeon may not be as aggressive in suturing the patch in place. This may leave a small residual hole. Fortunately, the vast majority of small residual VSD's seal up on their own over time. They almost never cause any problems.

All patients who undergo heart surgery are required to take antibiotics before any dental or surgical procedures for at least 6 months following surgery. The manipulation of the heart and the presence of synthetic tissue in the heart increases the risk of infection at any time bacteria may enter the bloodstream. This can happen with dental work and certain forms of surgery. After 6 months, usually the normal heart tissue has sealed things in place sufficiently to no longer require this.

The vast majority of patients who undergo VSD surgery do very well long-term. For many this is the only surgery they will ever require! Most patients are able to return to full activity within several weeks. The long-term prognosis for a patient who has had a VSD closed surgically is excellent.